The story of hippie fashion is often reduced to a few visual clichés: tie-dye t-shirts, flower crowns, and round sunglasses. But to view it through such a narrow lens is to miss the profound cultural earthquake it represented. Hippies did not dress to be admired. They dressed to be ungovernable. In a world that demanded uniformity, they offered chaos. In a society that valued polish, they celebrated the raw and the undone. This was the moment when fashion stopped asking for permission and started demanding freedom.

The Origins of Rebellion

To understand the clothes, one must understand the context. The 1960s were a pressure cooker of social and political tension. The Vietnam War was raging, the Civil Rights movement was challenging centuries of systemic racism, and a generation of young people was growing disillusioned with the "American Dream" their parents had bought into. The rigid social structures of the 1950s-where men wore gray flannel suits and women were confined to restrictive girdles and A-line dresses, felt like a prison.

The youth of the counterculture saw this uniformity as a symptom of a sick society. If the establishment wore suits, they would wear rags. If the establishment valued synthetic, pristine fabrics, they would wear natural, weathered cottons. Every sartorial choice was a negation of the status quo. This was not just about style; it was about survival of the spirit.

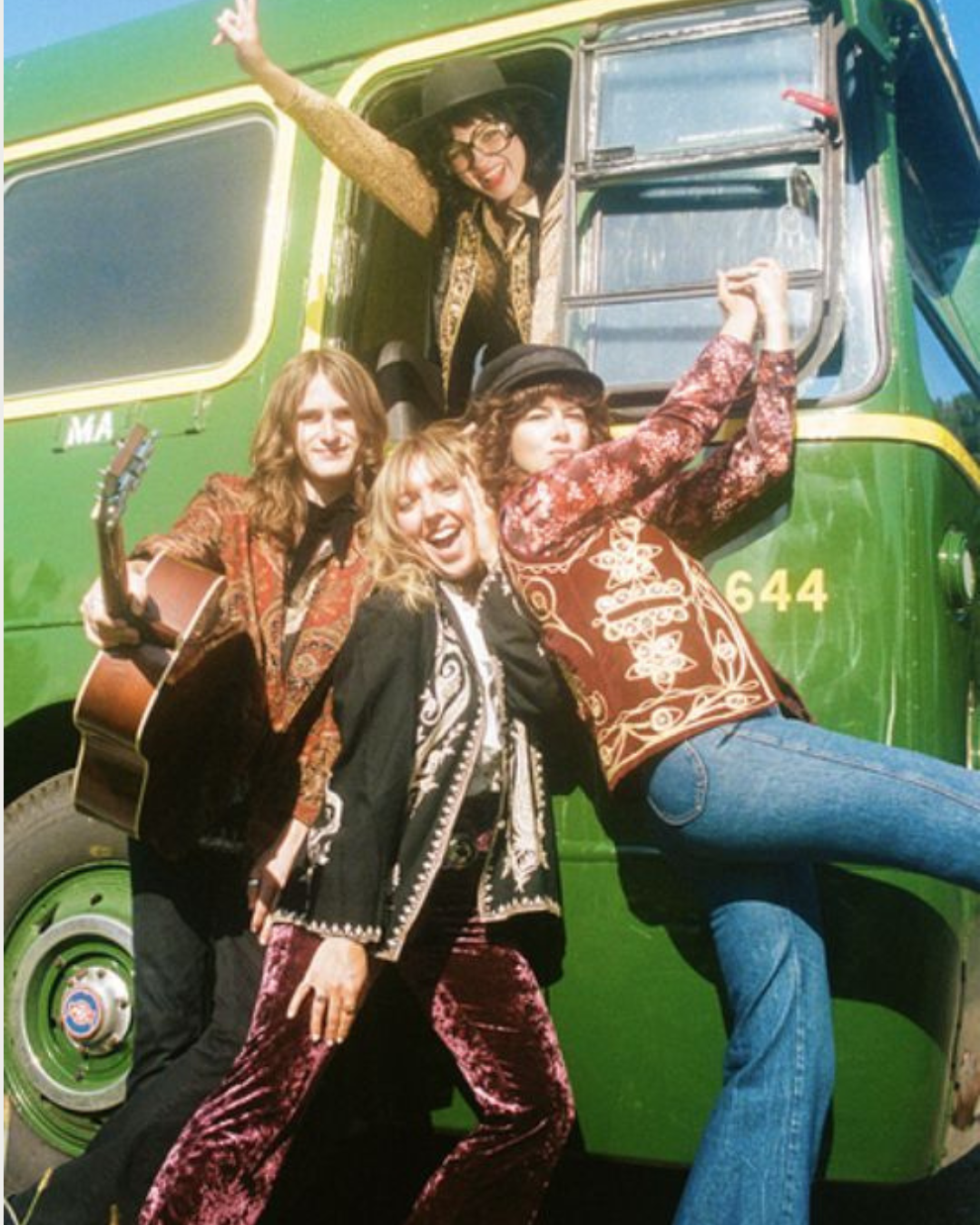

The movement had no central leader, no manifesto, and certainly no creative director. It bubbled up from the streets of Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco, the corners of Greenwich Village in New York, and the parks of London. It was organic, messy, and deeply personal. Unlike the fashion system that dictates trends from the top down, hippie style was a bottom-up revolution. It was democratic in the truest sense, anyone could participate, and creativity was the only currency that mattered.

Deconstructing the Silhouette of Control

The most immediate visual shift was in the silhouette. For decades, Western fashion had been obsessed with structure. Tailoring was designed to discipline the body, to hold it in, to reshape it into an idealized form. Men’s suits were armor; women’s undergarments were cages. The hippies rejected this entirely.

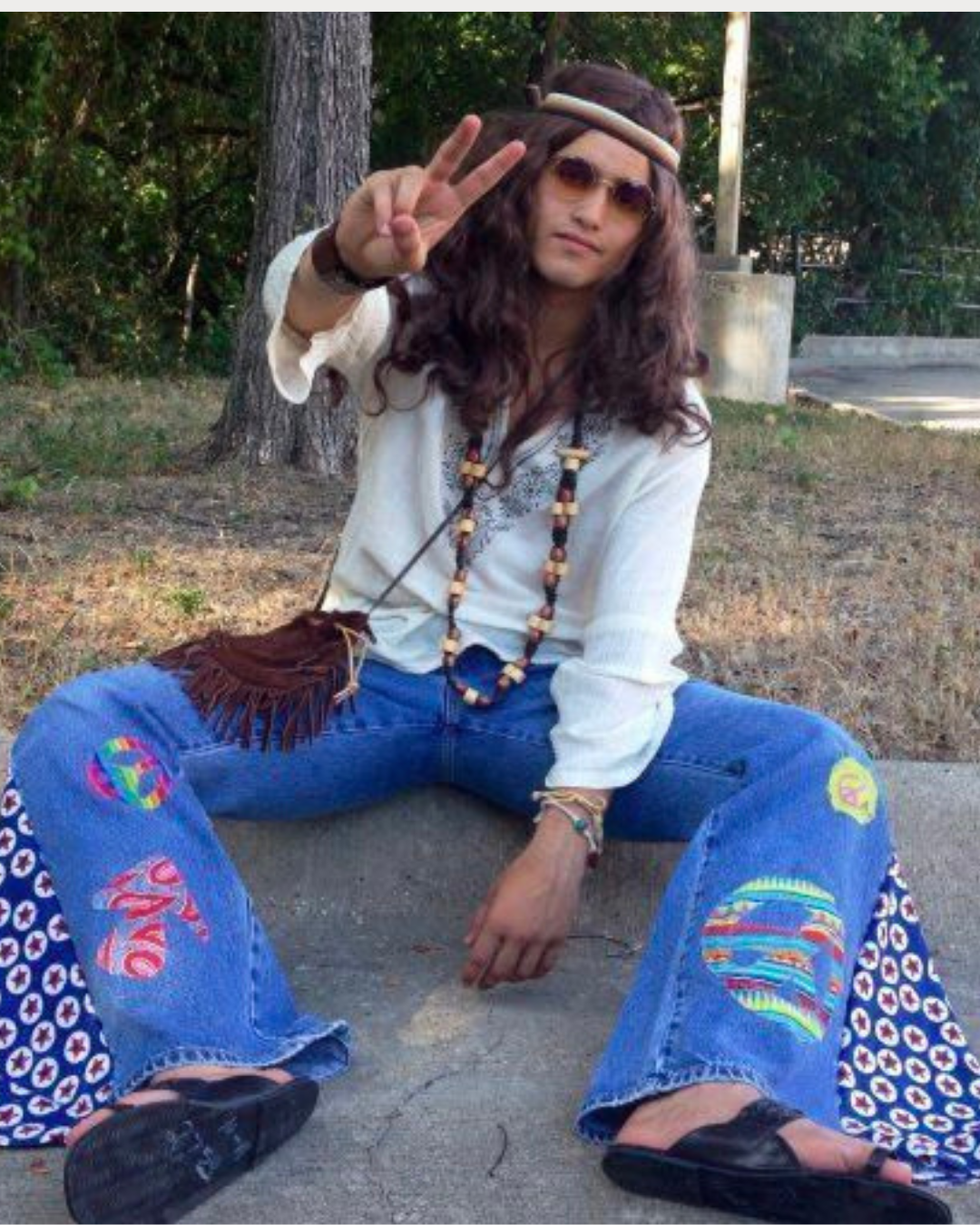

Loose, flowing silhouettes replaced tailored structure because tight clothing symbolized restriction, both physical and ideological. If you were going to free your mind, you had to free your body first. Bell bottoms were not just playful flares; they were garments built for movement, for dancing at concerts, for protesting in the streets, for sitting cross-legged in a park. They allowed the wearer to take up space in a way that straight-leg trousers did not.

This rejection of structure extended to gender norms. The "Peacock Revolution" saw men embracing color, pattern, and softer fabrics, challenging the drab uniformity of masculinity. Women, conversely, adopted jeans and work shirts, rejecting the performative femininity that had been imposed on them. The lines blurred.

Every oversized shirt, every flowing maxi skirt, and every layered look was a refusal to conform to imposed norms. The body was no longer an object to be displayed for approval; it was a vessel for experience. Comfort became a political priority. If you were comfortable, you were present. If you were present, you were powerful.

The Aesthetics of the Undone

Perhaps the most radical aspect of hippie fashion was its embrace of imperfection. In the 1950s, a "well-dressed" person was polished. Clothes were pressed, shoes were shined, and nothing was out of place. The counterculture flipped this script. What appeared "undone" was intentional.

Wrinkles were not flaws; they were evidence of life. Frayed hems were not accidents; they were a rejection of the industrial machine that demanded identical, flawless products. Dust, wear, and visible aging were proof that garments were lived in, not just owned. If something looked too polished, it meant the system had touched it. Perfection was suspicious. Imperfection was honest.

This aesthetic of the "undone" aligned with the movement’s anti-capitalist ethos. Why buy something new when you could mend something old? Patches became badges of honor, signaling that you had repaired a garment rather than discarding it. Embroidery was used not just for decoration, but to cover holes and tears, turning scars into art. This was the precursor to modern sustainable fashion, a rejection of disposable culture in favor of longevity and care.

The materials mattered as much as the message. Natural fabrics, cotton, wool, hemp, linen, replaced the futuristic synthetics like polyester that were being pushed by the industry. Synthetics represented the artificiality of modern life; natural fibers connected the wearer back to the earth. They breathed, they aged, they softened. They felt human.

Handcraft as Resistance

In a world that was becoming increasingly mechanized and mass-produced, the hippies turned to the hand. Handcraft was a form of resistance against the dehumanizing effects of industrial capitalism. If the machine wanted to make a million identical shirts, the hippie would make one shirt that looked like nothing else on earth.

Tie-dye is the most famous example of this. It was cheap, accessible, and inherently unpredictable. No two tie-dye shirts were ever the same. It was a celebration of chance and chaos in a world that craved order. But it went beyond tie-dye. Macramé, crochet, knitting, and leatherwork exploded in popularity.

People began making their own clothes or altering what they found in thrift stores. The thrift store itself became a temple of style. Before the 1960s, buying second-hand clothes was largely a sign of poverty. The hippies reframed it as a sign of discernment. Wearing a vintage military jacket or a Victorian lace blouse was a way of stepping out of the current time and referencing history. It was a collage of eras, a visual sampling that predated hip-hop’s musical sampling.

Embroidery became a key signifier. Jeans were no longer just blue denim; they were canvases for flowers, peace signs, slogans, and psychedelic patterns. This personalization meant that your clothes were an extension of your identity, not just a product you bought. Individuality mattered more than efficiency. Uniformity was the enemy.

No Trends, No Seasons, No Masters

Hippie fashion rejected hierarchy entirely. There were no trends, no seasons, no authority dictating what was in or out. Vogue did not tell a hippie what to wear; their community did. Style was not aspirational in the sense of trying to look rich or powerful. It was ideological. What you wore signaled what you refused to participate in.

If you wore beads, you were signaling an affinity with non-Western cultures and spiritual practices. If you grew your hair long, you were rejecting the military buzzcut and the corporate side-part. If you went barefoot, you were rejecting the literal separation between man and earth.

That is what unsettled the fashion industry. For the first time, clothing was not selling a dream of upward mobility. It was expressing dissent. Fashion houses could not control it. They couldn't monetize it at least, not initially. The power was no longer top-down. It belonged to the wearer.

The industry scrambled to catch up. Designers like Yves Saint Laurent eventually incorporated "peasant" looks and safari jackets into their high-end collections, sanitizing the rebellion for the bourgeoisie. But the raw energy of the street remained elusive. You could buy the look, but you couldn't buy the ethos.

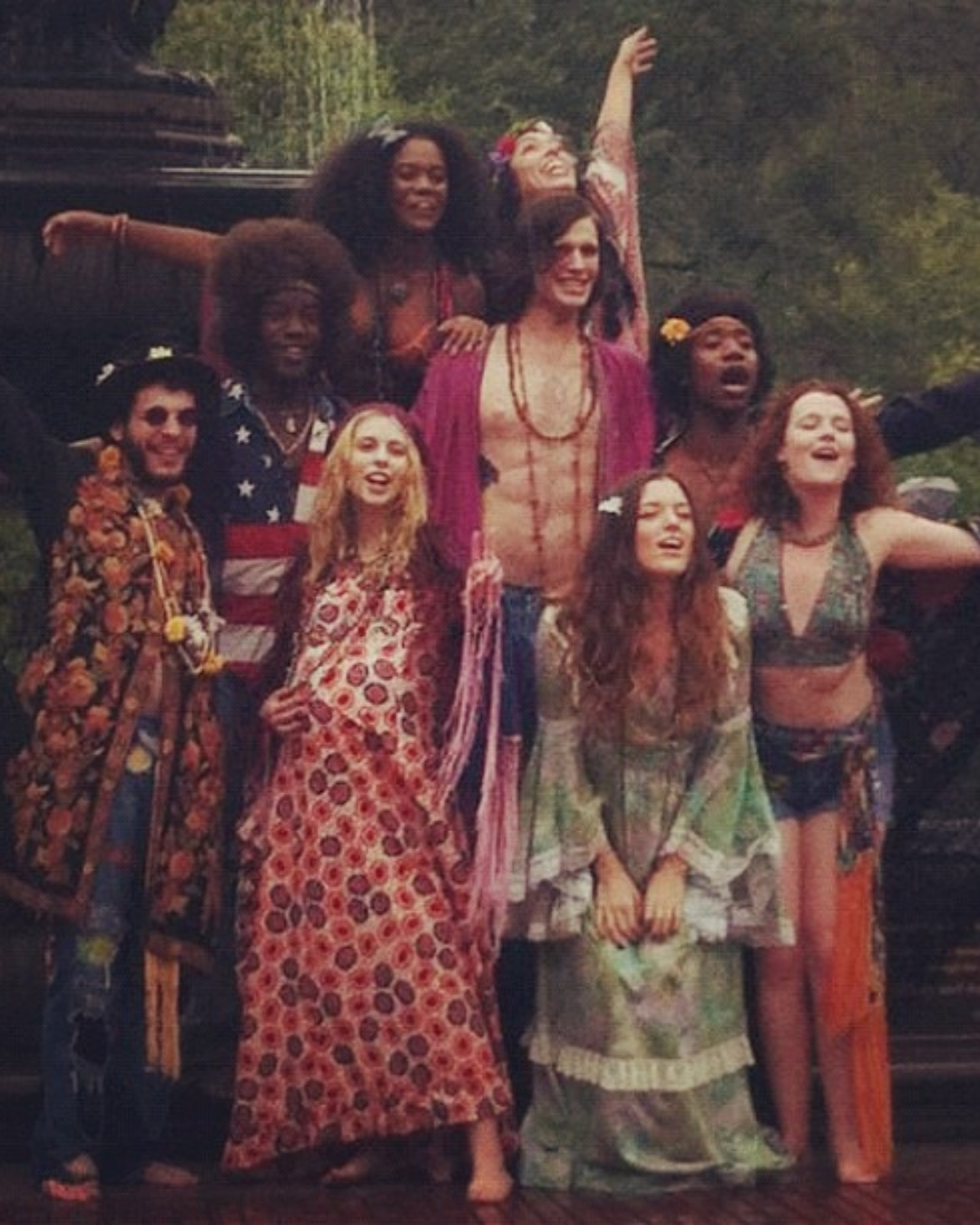

Global Influences and Cultural Exchange

The hippie trail, the overland route that many young Westerners took through Europe to South Asia, had a massive impact on the fashion of the era. Travelers brought back kaftans from Morocco, paisleys from India, shearling coats from Afghanistan, and ponchos from South America.

While today we view some of this through the critical lens of cultural appropriation, at the time, it was framed as a rejection of Western imperialism. By adopting the dress of the "Global South," hippies were attempting to align themselves with cultures they viewed as more spiritual, more connected to nature, and less corrupted by capitalism.

This influx of global textiles introduced new patterns, textures, and silhouettes to the Western wardrobe. The rigid, monochromatic palette of the mid-century gave way to a riot of color and print. It expanded the visual vocabulary of fashion, proving that there was no single "right" way to dress.

The Legacy of the Unruly

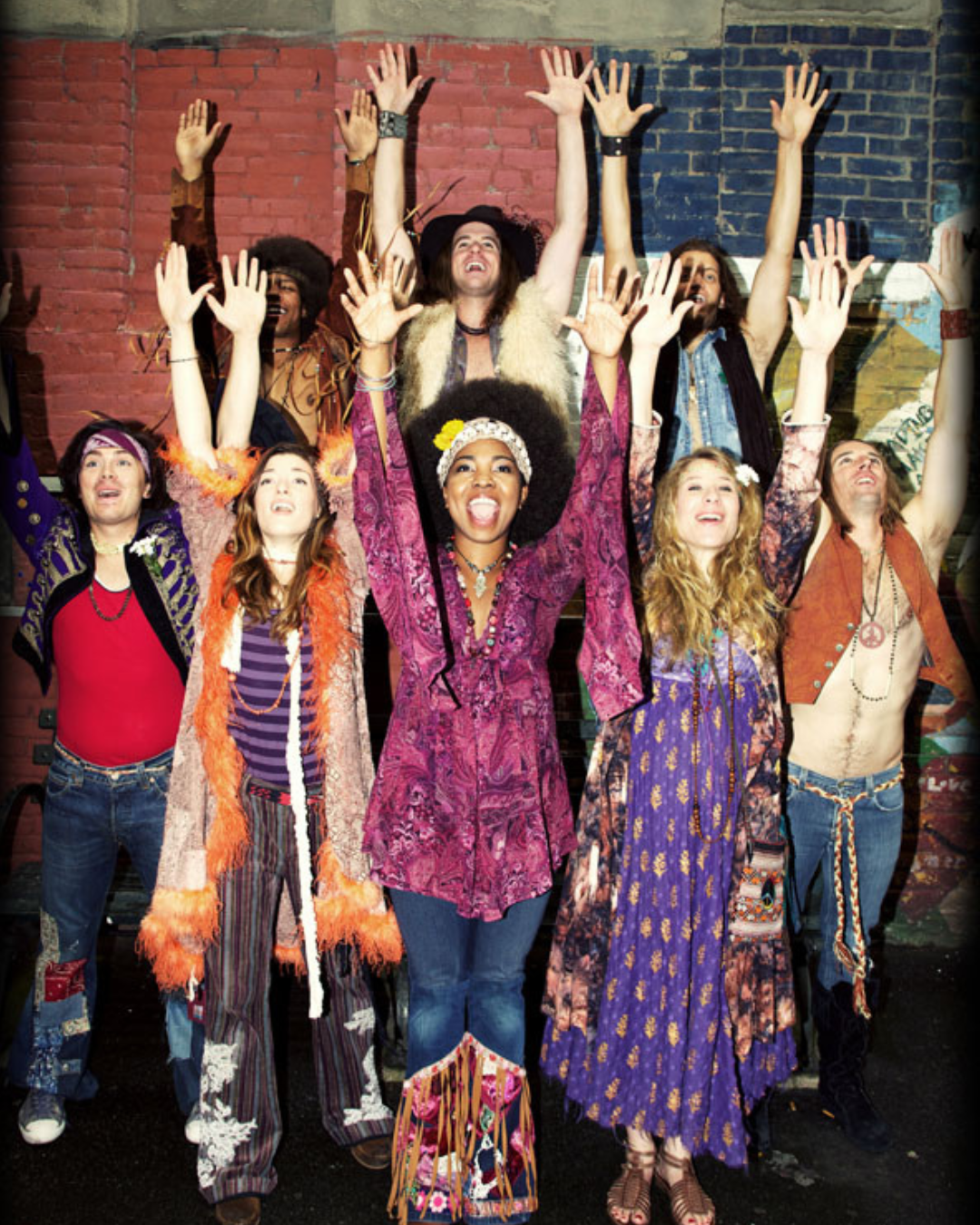

Hippie culture proved that fashion does not always want to be beautiful in the conventional sense. Sometimes it wants to be loud, messy, confrontational, and uncomfortable. Sometimes it wants to challenge systems instead of serving them.

And that shift changed fashion forever.

Long after the movement faded, its impact remained. Every time a designer sends an oversized silhouette down the runway, they are referencing the freedom of the 60s. Every time we see "distressed" denim sold at a premium, we are seeing the commodification of the hippie aesthetic of the undone. The current obsession with "cottagecore," sustainability, and upcycling is a direct lineage to the counterculture’s values.

The concept of "personal style"—the idea that you should dress for yourself rather than to fit a standard—is a gift from the hippies. Before them, there was a "look" for the season. After them, there were infinite looks. They broke the monolith of fashion into a million fragments, allowing us all to pick up the pieces that resonate with us.

Modern Echoes: The Gen Z Connection

It is no coincidence that hippie fashion is resonating so deeply with Gen Z today. The parallels between the late 1960s and the 2020s are striking. We are once again living through a time of political polarization, social unrest, and existential threat (climate change replacing the nuclear threat).

Young people are once again questioning the systems they have inherited. They are rejecting fast fashion in favor of thrifting and Depop. They are embracing gender-fluid clothing. They are using style as a form of activism. The "indie sleaze" revival and the chaotic layering of modern street style share DNA with the hippie ethos of "anything goes."

When a teenager today crochets their own top or paints their jeans, they are participating in the same ritual of resistance that their grandparents did. They are saying, "I am not a passive consumer. I am a creator."

A Lesson in Authenticity

Ultimately, the lesson of hippie fashion is one of authenticity. It teaches us that style is not something you buy; it is something you inhabit. It is the externalization of your internal world.

The hippies were not trying to be "cool" in the way we understand it today. They were trying to be real. They were trying to connect—with each other, with the planet, and with a higher consciousness. Their clothes were the uniform of that search.

Today, as we navigate the "metaverse" and digital fashion, the grounding nature of the hippie aesthetic offers a necessary counterweight. It reminds us of the value of the physical, the handmade, and the imperfect. It challenges us to find beauty in the fraying edges of life.

So, the next time you put on a pair of worn-in jeans or an oversized vintage tee, remember that you are participating in a lineage of dissent. You are wearing the legacy of a generation that looked at the world, decided it wasn't good enough, and decided to dress for the world they wanted instead.

They refused to ask for permission. Perhaps we shouldn't either.